The 11 best films of 2010 +1

Tuesday, February 1, 2011 at 08:53PM

Tuesday, February 1, 2011 at 08:53PM by David N. Meyer

THE GHOST WRITER

(France, Germany, United Kingdom)

Dir. Roman Polanski

“Confess! How many times did you watch Aguirre, The Wrath of God?”

“Confess! How many times did you watch Aguirre, The Wrath of God?”Polanski understands structure. Few directors remain whose poetry and narrative depend on knowing why one line demands a close-up or how a tiny gesture changes the universe or how to dramatize moments that bear no inherent drama, but prove later to be crucial notes in the symphony. Polanski’s pacing matches his formal genius; his scenes unspool so naturally, with such a light hand on the reins, but his narrative momentum never flags. A cynical, finely-wrought, intellectual, politically sophisticated suspense thriller/character study—seen many of those lately?—demands a master formalist, and a worldly, corrupted point of view. Does that sound Hitchcockian? It should. While Kim Catrell and her embarrassing U.K. accent defy casting logic (must be some investor dough coming in behind her), Olivia Williams provides the revelation. After an early career of thankless support babes (the wife in The Sixth Sense) her prospects seem to have devolved into a succession of glasses-wearing spinsters (An Education). Here she plays the least-seen of all adult female characters: sardonic, articulate, sexually aggressive, demanding, and respected for those qualities. Ewan McGregor’s a star with brains, and it should surprise nobody that Pierce Brosnan can actually act. He certainly commands the screen. A terrifying Eli Wallach appears not so much as the Angel of Death, but as mortality incarnate. Ghost deserves an audience, and awards, too, if for nothing more than its noble lack of pandering. In Europe, it garnered both aplenty. Over here, nobody saw it.

“You can’t see the weapon I’m carrying.”

“You can’t see the weapon I’m carrying.”A PROPHET

(France) Dir. Jacques Audiard

In 1980, Maurice Pialat’s Policerevealed that French cops hated French Arabs, that the Arabs hated them back, and that their worlds were mutually incomprehensible. As urban Arabs gained control over what the urban French craved—drugs—the cops slowly accepted their nemeses. Police presents this as a moral victory for the Arabs. The unspoken revelation to most viewers was the entrenched unrepentance of the French Arab universe. Gone were the Jean-Pierre Melville days of cops and crooks as living mirrors. Now they gazed with fear and loathing across an unbridgeable divide.

2002’s Nil Pour Nil Contre (Cedric Klapsich) furthered this idea in a noir as social comedy. His small-time, small-scale Arab underworld was only working stiffs looking for kicks. That they lived—for all their good humor—in a perpetual state of resentful anger, with rage lurking under the surface, required no explanation. They were on the bottom looking up, the outside looking in. Crime was their self-expression and they were everywhere, fully French. Not the aliens presented in Police, but neglected French-identified proles coping with warring cultures within and without.

The Prophet hardly bothers to place its characters in a larger society; their prison happens to be a penitentiary, but it only echoes the world beyond the walls, a bigger prison with invisible fences. The metaphorical example –the only example - of what was for generations regarded as a racially ‘normal’ Frenchman is a corrupt guard—the useless former uberclass hanging onto its shreds of legitimacy by enforcing rules that everyone knows bend to the highest bidder. The embittered, imprisoned Corsican mobsters understand that the “real” French regard them as only slightly less subhuman than the Arabs. They cling to that difference as poor southern rednecks prided themselves on their social superiority to blacks—that is, homicidally.

Our protagonist, an illiterate Arab youth, knows only the law of the jungle, and he does what survival demands. At first, his sole tool is native cunning, but slowly he develops a broader sense of criminality and of the world. As the entrenched order moves aside, a culturally unified criminal force ascends—one that could care less about assimilation.

“Let’s take aim at the oppressive paternal power structure in them there hills.”

“Let’s take aim at the oppressive paternal power structure in them there hills.”WINTER'S BONE

Dir. Deborah Granik

Here the culture explored is not a rising criminal underworld separated by race and language from the dominant culture whose vices they feed, but a self-alienated sub-working class that turns to criminality not for riches nor to climb the ladder, but for groceries. Bone operates under shocking, admirable economies of unembellished story-telling and its themes emerge from the souls of its characters. The moral landscape appears as stark as the hills and as inescapable. Men rule women, violence overhangs every utterance, and if you want to survive, you better learn to gut squirrels. André Gregory says—inMy Dinner With André—“The prisoners are always happiest when they build the prison themselves.” And these poor white trash love their home, their ways, and the prison of pain they’ve built brick by brick and from which nobody ever escapes, or really, wants to. Oscar for Dale Dickey.

THE ECLIPSE

(Ireland) Dir. Conor McPherson

Ciarán Hinds is haunted by his recently dead wife. His house may or may not be. Aiden Quinn plays the biggest and most accurately drawn literary asshole ever. Iben Hjejle, last seen on these shores playing John Cusack’s girlfriend in High Fidelity, provides the sane, reticent love interest. And that’s it: a sad man, the shimmering Irish seaside, a ghost or two, and a little too much piano plinking away at the high end of the keyboard. It’s a thoughtful, unvain, adult love story, simply told and satisfying.

RESTREPO

Dir. Tim Hetherington,

Sebastian Junger

The directors embedded with U.S. troops in an isolated valley of Afghanistan. They stayed a long time, long enough to understate, which was never Junger’s way. The directors explain nothing, contextualize nothing, because what takes place defies explanation and the action is the context. They expect us to absorb it as they did, as if we were visiting Mars and translating words and events as fast as we can. Their lives depended on their translation skills. We get to watch.

The Brooklyn Rail would never pander to the baser instincts of our readers to increase circulation. Jamais!

The Brooklyn Rail would never pander to the baser instincts of our readers to increase circulation. Jamais!CARLOS

(France) Dir. Olivier Assayaz

Ché had no business being five hours; it felt overlong and under-motivated at two and a half. Carlos, which attempts, like Ché, to present the sweep of history as the product of one man’s neurosis and vice versa, earns its length. Assayaz could never be hurried, and he meanders here as ever. When his star can’t hold the screen, the director turns to Carlos’s seemingly endless remuda of exquisite, brainy, astringent Euro-babes, and lets them carry the moment. In this way, Assayaz proves not unlike Carlos. Assayaz takes a singular, and far from compassionate view of the terrorist; he presents Carlos as a driven naïve artist, compelled early on by pure ambition, then by lust for fame, and finally rotting in his dotage, which arrived earlier than expected, since history had no more use for him. When his accomplishments didn’t quite stack up to his rhetoric, Carlos turned annoying. His comeuppance seems more rooted in being a pain in the ass than in any act of terror.

FISH TANK

(United Kingdom) Dir. Andrea Arnold

English adolescent working class rage takes a different path than its Ozarkian counterpart, apparently. In the U.K., it turns inward. Amateur Katie Jarvis creates all the problems and provides all the solutions in this by turns awkward and mesmerizing low-budget neo-realism. Kierston Wareing portrays the toxic, desperate, fading-away party mom of all time, and the director lets her get thisclose to being sympathetic before mom’s ugliness—born of the same frustrations that have doomed her daughter—resurface. A study in lifestyle and class, and thus more attentive to detail than action, but the detail stands up for itself. As does Katie, until she just can’t.

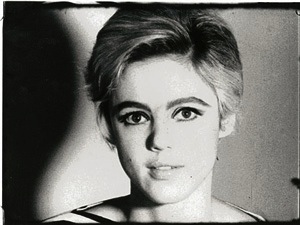

“I can do studious and tormented.”

“I can do studious and tormented.”THE AMERICAN

Dir. Anton Corbijn

Video master Corbijn’s (Madonna,U2, Depeche Mode, Metallica) an adult now, and so is Clooney. Here they reach for adult themes: moral failure, impending mortality, craft and how it armors the soul against the disappointments of life, the unlikely connections that make the latter worth living, and the unworthy temptations that failure teaches adults to avoid. When Clooney’s not playing buffoons for the Coen brothers, he vests in scruffy, tormented, emotional fugitives, as if they provide absolution for being a movie star. He taps into his not-immediately-apparent alienation, evoking the best of Jimmy Stewart. Corbijn reaches so avidly for mood over narrative that you want to deny the gestalt he seeks, just to spite him. Only, every now and then, Corbijn gets what he’s after and so does his star. The picture fails on its own terms as a character study and a suspense thriller, but so what? The transcendent Italian locations, the understated score, and Clooney’s quiet desperation provide whatever truth the script can’t quite deliver.

OSS 117 LOST IN RIO

(France) Dir. Michel Hazanavicius

The French make better Austin Powers movies by never winking at the audience, by willing to be political, and by featuring a hero every bit as racist, misogynist, oblivious, and sociopathic as, say, Ian Fleming’s in-print James Bond. The second in the Lost series, starring the deadpan, world-class smirker Jean Dujardin, seeks out ex-Nazis in an early 1960’s Brazil populated exclusively by bikini- and go-go girls. The fashion, color palates, closeted homoeroticism and plot lines evoke the era without adding any sophistication, which, like everything else in the picture, charms. Oddly unseen on release, now even more oddly available on Netflix Instant.

LA LOI

(France -1959) Dir. Jules Dassin

Ah, operatic S&M class critique in the Italian sea-side boonies: torn black silk slips and slaps to the face, Gina Lollobrigida tied down and whipped with belts (by her sisters!), Melina Mecouri discovering the pleasures of pain and everyone as trapped in the wheels of tradition and township as the po’buckers in Winter’s Bone. They dress better, of course, they’re Italian. Jules Dassin had himself some issues, and no shortage of rage. He lets it all out, composed in theatrical frames whose ornate structure belies his characters’ unstoppable intertwining of love and malevolence.

VALHALLA RISING

(Denmark) Dir. Nicholas Winding Refn

Can a broody Viking movie avoid evoking death metal videos? Apparently not. Can white explorers invade aboriginal turf without evoking Aguirre, The Wrath of God? Negatory. Other than Polanski, Refn is the most astute, concise structualist directing today, a master of form and tautness (cf. Pusher, Pusher II, Pusher III). That Valhalla wanders more than its ocean-crossing protagonists provides its primary disappointment and irritation. Why then, is it so addictively watchable—even while being dull? (Aside from the promise of a swordfight or two, of course) Why do images linger in the mind as if dreamed by the viewer? Refn’s a modern literalist; he’s not a fable kind of guy. And even though myths usually have plots, Refn incongruously gets ahold of something that feels awfully close to mythology.

Special Mention:

SPARTACUS: BLOOD AND SAND (Starz Network)

I keep asking myself: even given the expansion of scope that’s the nature of a series, and the attendant opportunities for in-jokes, character development, and suspense/themes sustained over weeks, are any of the films on this list more daring, unhinged, satisfying, committed, or as complete a narrative entity asSpartacus?

Only a couple, and neither of them are as much fun.