"CAN'T YOU SPARE ME OVER ANOTHER YEAR?"

Wednesday, November 23, 2011 at 06:27PM

Wednesday, November 23, 2011 at 06:27PM THE PHANTOM CARRIAGE CRITERION DVD

Victor Sjöström’s Death has a tough gig. He drives the Phantom Carriage – a rotting wooden-wheeled wagon pulled by a decrepit horse - and gathers up dead souls. Death didn’t apply for the job, either. Reflecting perfectly pessimistic Swedish predestination, whomever dies nearest to midnight on New Year’s Eve becomes Death. Death serves, like Miss America, for one calendar year. The following New Year, some other poor dead sucker inherits the cowl and scythe and takes the reins.

Of course, Ingmar Bergman pretty much has a lock on the default image that comes to mind when you hear the phrase ‘Death incarnate’: the black-robed, pale-faced, frog-eyed specter who challenges Max Von Sydow to a chess match in The Seventh Seal. His urbane manners and abiding patience make him creepily familiar. He’s one scary, passive-aggressive father figure and no one who sees the film forgets him.

Swedish cinema titan, technical innovator, director, leading man and cranky bastard Sjöström - Bergman’s idol, mentor, bête noir, occasional father figure and cast regular - knew a thing or two about Death. Embracing his mortal terror, Sjöström adapted Nobel Prize winner Selma Lagerlöf’s novel and cast himself in the lead. Criterion delivers an immaculate print of Sjöström’s 1921 moral melodrama and special effects tour-de-force The Phantom Carriage, which Charlie Chaplin cited as the greatest film ever.

Unlike Bergman’s archetype, Sjöström’s Death has neither manners nor patience. He’s tetchy and wore out, and little wonder, what with creaking hither and yon 24/7, chucking another soul into the carriage and rattling on to the next. In lesser hands, that would be the tale. But for Sjöström, as for Bergman decades later, Death is a means to an end, a prism through which to view the real story.

That story involves drunkenness, the Salvation Army (!), a forbidden love that does not fear Death, a love that lives beyond it, redemption (of course), and some hard-earned self-forgiveness. Yes, it’s a weeper, and should by description be a little ridiculous. But, like D.W. Griffith, Sjöström offered a gift to the future: the expressive force of his close-ups. The poetry and realism of Sjöström’s compositions - his placement of characters static and in motion – and the power of the faces of his cast create archetypal images of which Death is not even the most memorable. Sjöström had a profoundly modern grasp of what makes inhabited cinematic space. His influence on both Chaplin and Bergman is plain. The emotional truth of his frames overwhelms the melodrama of his plot, most of the time anyway.

Sjöström plays David Holm, a violent, reprehensible, endearing alcoholic. He had an enormous, mobile, dramatic face, as did all his co-stars. Sadly, no 90-year-old film draws a modern soul completely into the narrative. Much of the fine acting plays at a remove, until one of several wrenching moments crosses the divide of nearly a century. One of the more startling moments features Sjöström, in a drunken, psycho frenzy, bashing through a door with an axe so he can attack his terrified wife. Stanley Kubrick copped this assault chop for chop for chop in The Shining.

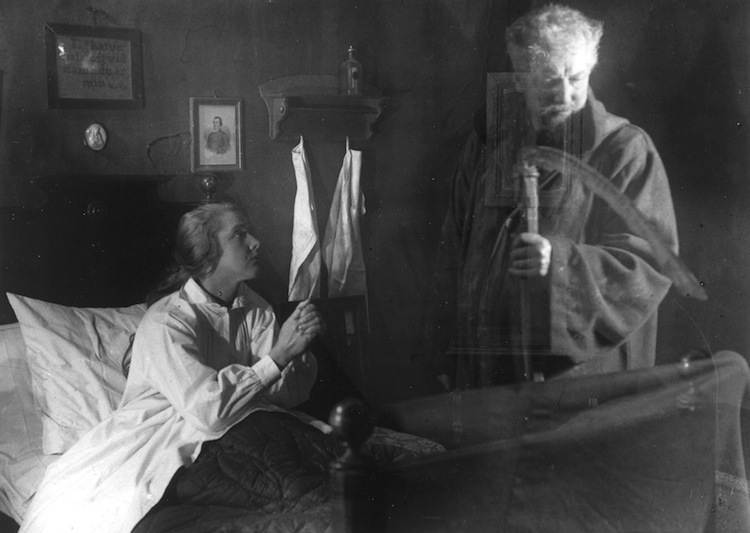

The Phantom Carriage creates ghosts and their interaction with the living through then groundbreaking special effects utilizing triple and quadruple exposures. They’re among the most evocative of their kind, consistently fascinating, and they help sustain attention during the most melodramatic moments. These see-through figures inhabit the mind well after the movie ends. This has been my experience of most of the great silent films, like Murnau’s Faust; I watch at a distance, never immersed, but later, image after image recurs with surprising clarity.

Criterion’s DVD extras provide crucial context and history. There’s a lugubrious, revealing interview with Bergman about his relationship with Sjöström (Bergman bugs the hell out of me); a superb essay on Sjöström’s life and career by Peter Mayersberg, the genius who wrote Croupier; and an understated, almost perfectly appropriate score by composer Matti Bye. The score, recorded live at a public screening of Carriage, leaves the melodrama to Sjöström. The sophisticated of the score echoes how unnecessary to the drama – not the melodrama – the spoken word title-cards become. Sjöström was a visual storyteller, and the entire tale is right there in the frames.