HELL OR HIGH WATER

Tuesday, August 23, 2016 at 11:53AM

Tuesday, August 23, 2016 at 11:53AM Debts No Honest Man Could Pay

Ben Foster and Chris Pine Photo Credit: Lorey Sebastian

Ben Foster and Chris Pine Photo Credit: Lorey Sebastian

Hell or High Water is a sneaky-profound, accomplished, very welcome resurrection of a favorite exploitation genre that tragically disappeared: the mid-1970’s, widescreen, stick-it-to-the-Man, shoot-em-up with a Message. A bleak revisionist Western, Hell plays – as intended – like a modern country song. But not a cornball Nashville nursery rhyme like something by Toby Keith. At its best, Hell becomes a self-aware, hard-edged lament by Jason Isbell or Sturgill Simpson – a bloody ballad, cadenced and elegiac.

Or, given Hell’s intertwined hope and defeat, it’s pure narcocorrido.* It has all the elements: a good man gone bad for good reason; a bad man who does not want and knows he does not deserve redemption; a fatherly law enforcement figure whose soul vengeance turns to ice and his “half-breed” partner at home in neither the white nor his native world. Each of their tales fuel a yearning for a lost time and place, a yearning for what coulda shoulda woulda.

The Man getting it stuck to is a Texas bank about to foreclose on the family home of two brothers, Ben Foster and Chris Pine. They set out to rob the bank of enough cash to pay off the mortgage. The bank wants to foreclose to exploit soon-to-begin oil leases; the brothers have to stop the bank, ditto.

Illuminating the theme of disenfranchised working-class whites caught in the cogs of oppressive big business, the brother’s success would bring a double payoff: screwing the bank screwing them and cashin’ in on that oil lucre like the invisible fat-cats who pull the strings that ruined their lives.

Chris Pine slouches around all monosyllabic gazing sideways into the middle distance, doing his best Chris Hemsworth impression, and it’s pretty good. Ben Foster performs the heavy lifting and so talks non-stop. He occasionally wrecks the taut atmospthere by speaking the film’s themes aloud. At times the two seem like actors who just met trading lines. But at crucial plot moments, their chemistry ignites. Fortunately, their less convincing exchanges come in the first quarter of the film.

The yin to their yang are Texas Rangers, a revelatory Jeff Bridges, accompanied by Gil Birmingham as his wisecracking partner. Insult-swapping cops is an ‘80’s, not a ‘70’s trope, but exploitation demands suppression of male to male affection no matter what the era. Like the bros, the most loving thing the cops can say to each other is: Fuck you. The story crosscuts between the two sets of bros with precision timing and suspense. As in any worthy ballad, rhythm is Hell ’s strong suit.

Hell is men in a man’s world. There is no romantic subplot. Women appear briefly. They’re all so fed up with manly antics they can barely lift their eyebrows in resignation; a Greek chorus of women who find macho posturing tiresome and ridiculous. That's not the usual role for women in a Western, to say the least. Malin Ireland, playing Pine’s former wife, steals every scene with her laden silences. A lesser film would offer hints of reconciliation. But in this hardscrabble landscape, there ain't no do-overs.

In the most powerful sequence, the brothers race out of a robbed bank to discover exactly what awaited the Jesse James-Cole Younger gang when they emerged from a plundered bank in Northfield, Minnesota in 1876:** an armed populace hype to blow their heads off. Pine and Foster met a pistol-packing Texan in an earlier robbery and escaped as he emptied his clip – even though they made of point of not taking his cash. Hell captures the seething, hair-trigger resentment of disenfranchised flyovers with Conceal Carry permits. It’s a sophisticated irony and a mid-‘70’s flashback that the trigger-happy Texas rednecks can’t recognize the brothers as their potential allies in armed revolt. The underemployed rednecks’ impotent rage makes them rejoice at a chance for legal murder. Their cold-blooded, gleeful fusillade speaks volumes about the contemporary electorate. And about how mid-‘70’s message shoot-em-ups always showed society rejecting their heroes.

The brothers race away from the bank and Hell presents a moment you’ve never before seen in a Western. Instead of horses, the armed posse fire up their pickups and SUVs and give chase. As the brothers return fire, civilian blood-lust explodes. Bridges by this time has his own reason to kill, and his performance becomes astonishing. He’s been mailing it in for a while, but here brings levels of Old Testament righteousness, of mixed grief and triumph, even his long-time fans never suspected he could never pull off. Watching him Ranger and wise-crack and be hard-bitten all over Texas of course brings to mind Tommy Lee Jones in No Country For Old Men. Maybe that intimidating example inspired Bridges.

No Country looms large over Hell. Margaret Bowman – the motel clerk who can’t believe Josh Brolan wants more than one room – appears as a tough-ass waitress. She’s funny, but insists the only choice available today is what you don’t want. When secondary characters speak more than one sentence at a time – which is rare – they describes the loss of a cherished status quo. Their language is rueful and clean, Cormac McCarthy Lite. Their tiny speeches never hit a false note; they’re singing three-sentence ballads of defeat. Okay, it’s a message Western; somebody’s got to deliver the Message.

Hell’s clumsy moments do not overwhelm its grace notes. There are plot-holes as wide as the Texas sky pushed aside by scenes right out of Jean-Pierre Melville. Foster’s best moment comes in a confrontation with a scary Native American in a casino. Foster offends him on purpose, then tries to show their affinity. The Native American, like a prideful gangster in a French Noir, is not appeased. Echoing the women, he’s had a sufficiency of swaggering broke-ass cowboys.

Hell suffers when it hits you over the head with its themes. The posse scene proves memorable because there’s no attempt at commentary. Nick Cave’s score finds the exact tone between pastoral and dread. Unfortunately, every country song on the soundtrack is wrong-headed, too on-the-nose and distracting. The film tries to use the songs to underscore emotion the scenes already evoke. The opening number – a Townes Van Zandt song that sounds nothing like Townes – and the song over the closing credits are the most egregious offenders. Each bad song hurls you out of the story.

At first Bridges was bemused, as was Pine, at what seemed to both a game. Come to the end, and neither’s assuaged the anger that fuels a war between them. The finale is bold and carefully wrought – a truly great exploitation set-piece. Director David Mackenzie, who showed no fear of ambiguity in his under-seen Young Adam, revels in the unresolved ending. Unresolved because the saga changed Bridges and Pine. Each now sees the other – failed law enforcement vs. homegrown anarchy – as the source of his ruin. There is no simple solution and the film doesn’t stoop to provide one.

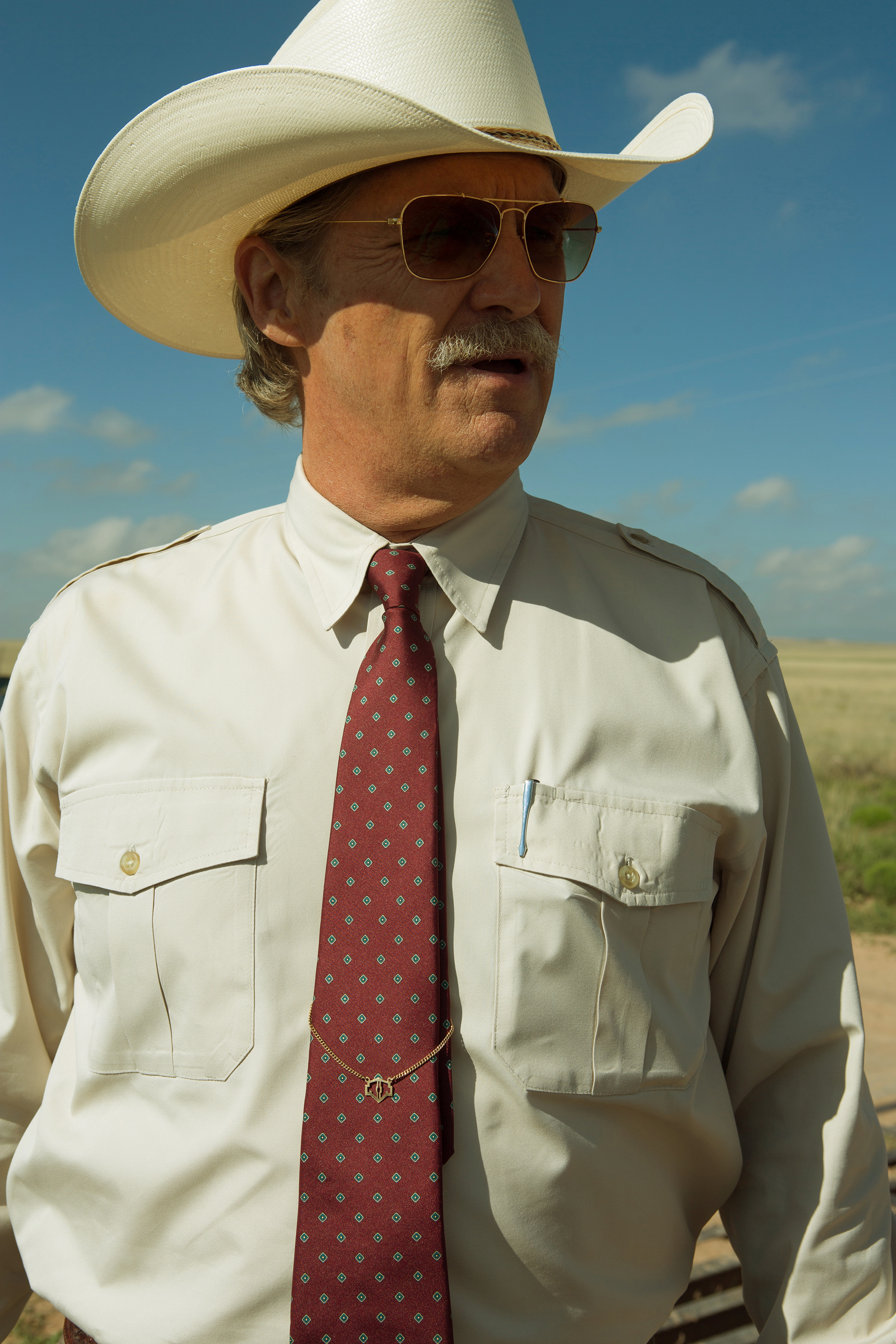

Jeff Bridges Photo Credit: Lorey Sebastian

Jeff Bridges Photo Credit: Lorey Sebastian

* Like this one from Breaking Bad https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BUmpTKXpIdM

** cf. The Great Smithfield, Minnesota Raid https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zw4eL-LNejs

or

The Long Riders https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1hs1ZR3uIHw

or

Better yet, read Ron Hansen’s Desperadoes https://www.amazon.com/Desperadoes-Ron-Hansen/dp/0060976985/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1471906820&sr=8-1&keywords=desperadoes

Ben Foster,

Ben Foster,  Chris Pine,

Chris Pine,  Gil Birmingham,

Gil Birmingham,  Jeff Bridges,

Jeff Bridges,  Westerns,

Westerns,  Young Adam

Young Adam