BUT FOR WHAT YOU ARE NOT: 13 MOST BEAUTIFUL...ANDY WARHOL SCREEN TESTS

Thursday, October 7, 2010 at 01:42AM

Thursday, October 7, 2010 at 01:42AM 13 Most Beautiful...Songs for Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests, Dean & Britta, Los Angeles Film Festival, Ford Amphitheatre, June 30, 2009

It’s impossible to watch Andy Warhol’s Screen Tests without comment. As Pauline Kael said of Godard, the Tests turn an audience into film critics. And art critics, amateur shrinks, and fabulosity deconstructors.

Shot in two and a half minutes, and projected over four in Warhol’s slow playback method, the Tests are unblinking cinematic portraits of subjects told to “sit still and not blink.” By dictate, they do almost nothing. Lou Reed fondles and drinks from a beautiful mid-’60s Coke bottle and Baby Jane Holzer languorously, mischievously brushes her perfect teeth. That’s it. Everyone else stares back at the camera or into the middle distance or who knows where they’re gazing behind their impenetrable shades?

Those omnipresent shades (Lou rocks some fine wraparounds, Billy Name prefers big pilot-style Ray-Bans) are no less opaque than the portraits themselves. Cinema, portraiture, animated furniture—like so many Warhol films from this period, theTests just is. Though nothing happens in their content, their presence alters the molecules around them. They prove entrancing, tedious, inspiring, and fabulous: lost artifacts, gleaming communiqués rooted in a quite specific period and—if you knew no backstory—from no time at all.

Something in their stillness makes the mind race. Among the notions evoked: that Warhol imparts so much glamour and gravitas to his subjects it becomes impossible to tell who was famous/important/creatively productive and who was just hanging out; that methamphetamine—the Factory drug of choice—gave everyone the most razor-sharp cheekbones; that the women’s hairstyles so incarnate this era (1964–66) that one can practically identify the month and week of the shoot.

It’s oddly difficult to keep these notions to oneself through the almost endless four minutes that each portrait hangs, as it were, projected on a massive screen raised behind the stage of the 1929-era, cozily outdoor Ford Amphitheatre. And so the woman in front of me whispered her insights pretty much continually into the ear of her apparent boyfriend. Didn’t bother me—she spoke so softly that I never heard a word she said. But suddenly, about halfway through, a classic little old lady (classic in the L.A. style, which meant severe pedal-pushers, cool sneaks and a little sweater) popped across the center aisle from three rows down to shush the whispering woman. The chastened whisperer turned ’round to me—dunno why—to share outrage and surprise and I told her: “You’re the first person I’ve ever seen shushed at a rock-and-roll show.” When folks in L.A. are told they’re witnessing Fine Art, apparently they’re compelled to behave like they’re in a museum or at the opera. Or, more accurately, at a funeral. The shushing should have felt discordant and incongruous. But incongruously, it did not.

The gargantuan screen, the opiate Tests, the sweet L.A. evening air and the naively reverential audience generated a weird denial. Denial of the fact that Dean (Wareham, formerly leader of Luna) and Britta (Phillips, his romantic and artistic partner, formerly of Luna, co-star of the 1988 chick-band flick Satisfaction with Justine Bateman, Liam Neeson, Julia Roberts, and the singing voice of the animated heroine Jem) were onstage below the screen, rocking out, along with guitarist/keyboardist/bassist Matt Sumrow and drummer Jason Bemis Lawrence.

D & B were determined not to upstage the Tests. They did not want the film projected over them (like the Warhol films which poured over the Velvet Underground during the Exploding Plastic Inevitable), and so played in darkness, dwarfed by the static but constantly moving images over their heads.

Maybe because of outdoor venue noise ordinances, or an opera being performed live right across the Hollywood Freeway, at the Hollywood Bowl, the band rocked at a subdued volume. Though even in clubs Dean & Britta seldom shatter ears, here they sublimated themselves to the Tests, seeking music and presentation that formed a harmonious whole. They succeeded to an astonishing and transcendent degree.

A while back, the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh asked Dean & Britta to compose a score for a live show of the Tests. Warhol used to put Tests together for parties under the rubric of “The 13 Most Beautiful;” D & B honored that number. Dean went to Pittsburgh and watched over 150 tests. He took “between 30 and 40” home. He and Britta were at first intimidated into procrastination, then began to study the Tests with care as they narrowed their choices. The final selection took months. At one point D & B were watching dueling Lou Reed Tests simultaneously, trying to suss which seemed the most Lou-esque.

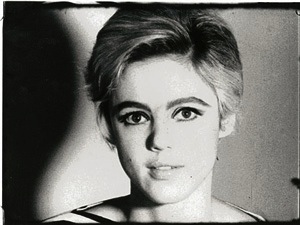

Dean said in interviews that he wanted “people who were at the Factory (Warhol’s headquarters on West 47th Street) every day.” He found even the most stunning one-offs, like Bob Dylan, to be less representative of the time and place, and of the soul of the Tests themselves. Dean and Britta finally chose to project and to compose original music for the Tests of Edie Sedgwick, Dennis Hopper, Paul America, Susan Bottomly, Ann Buchanan, Freddy Herko, Jane Holzer, Billy Name, Richard Rheem, Ingrid Superstar, and Mary Woronov.

For the radiant, doomed, terrifying Nico, the band played Bob Dylan’s ode to the blonde singer/model/femme fatale, “I’ll Keep It With Mine,” which features a couplet that could speak of everyone in the show:

“I’m not loving you for what you are / But for what you’re not…”

For the utterly I-don’t-give-two-shits Lou Test, they played a quite recently discovered Velvet Underground original “I’m Not A Young Man Anymore." Though the original’s a White Light-era VU rave-up, D & B rave more quietly, and demonstrate how perfectly their post-Luna sounds accompany the Tests.

As the Tests become animated paintings or furniture, neither wholly plastic art nor cinema, D & B’s music becomes dreamscape. After no more than a minute, the Tests morph into the view out of a moving car’s window onto an empty, desolate land that barely changes mile to mile, but somehow remains hypnotic. The score—sometimes meandering, sometimes howling with pain, sometimes funereal—proves rich in thematic material and functions as both the car and whatever’s on the radio during that unchanging 10-hour day behind the wheel. As one looks at the Testsand drinks them in without actually seeing, so the music permeates and nourishes without conscious listening.

The D & B visits the early Velvet Underground, show a strong Leone influence, recreate the sonic-scapes of (Wareham’s first band) Galaxie 500-ish noodling, and even put the pedal to the metal. But in keeping with the we’re-watching-art-now-please vibe, only one person in the Amphitheatre—me —showed any head-nodding, foot-tapping physical response to the music, and that included the band.

Dean set up most of the Tests by telling a little story about each’s subject. He told most, Britta told a couple. When Britta spoke of Ingrid Superstar’s real name, Dean corrected her onstage with much greater tact and ease than Britta utilized in gesturing tempo corrections at the drummer, which she did in no uncertain terms about every other song. Wareham is disconcertingly disengaged, or deadpan or catatonic, depending on your view. Rather than the spacey, dazed dislocation of David Byrne, which convinces the observer that he spent his formative years going around and around inside his mom’s dryer, Dean’s blankness seems to spring from simple natural cool. He spoke in a bemused monotone, and Britta responded to his correction as if they were sitting around their hotel room eating room service. It was a deeply Warholian exchange.

Dean and the other guys in the band dressed like indie rock schlubs, which in L.A.is a reach for anti-fashion cred. In most videos and photos, Wareham’s a bit of a clothes-horse, so his baggy pants and nondescript black oxfords were a surprise. Britta sported the Kim Gordon (Sonic Youth bass-player) uniform with ease: a shiny black mid-60s-evoking minidress and what seemed to be—under the dim stage lights—white thigh-highs and delicate to-the-minute evening sandals. Gordon, despite her I-will-kick-your-ass androgyny, seems softened by her chic, more accessible. As if Britta wasn’t already intimidating and cooler than thou (or certainly me), her oh-I-dress-like-this-all-the-time attitude, ethereal vocals, and willfully adorable faux-naïve keyboard riffs kicked her onto some otherworldly plane of can’t-touch-this-ness.

The most moving moment of the evening came when Dean spoke—like the coolest camp counselor ever at campfire story time—of Factory regular Freddy Herko, a dancer who gave up his career to shoot speed and live in a closet. One Sunday, people gathered for brunch in the fourth-floor walk-up loft that contained Freddy’s lair. Someone put on a Mozart Mass; as it peaked, Freddy emerged naked from the closet, dancing across the room. The Mass climaxed and Freddy, in one perfectly extended galvanic leap, soared right out the window to his death on the sidewalk below. As Freddy’s chiseled cheekbones flashed black and white against the L.A. night sky, the band played a gentle, murmuring dirge.

Billy Name,

Billy Name,  Dean & Britta,

Dean & Britta,  Freddy Herko,

Freddy Herko,  Galaxie 500,

Galaxie 500,  Godard,

Godard,  Kael,

Kael,  Lou Reed,

Lou Reed,  Nico,

Nico,  Velvet Undergound,

Velvet Undergound,  Warhol

Warhol